Some parting thoughts after visiting cuba

A reflection on the mixed blessings of Socialism in Cuba, and the 90 miles of melancholy that separates the U.S. and its risk-taking tropical neighbor

I started this trip in Miami’s South Beach, where the Miami Cubans have set the tone for how to take a blue-haired New York vacation spot and turn it into the throbbing heartbeat of hip America. The buildings in South Beach are worthy of a walking tour – but life on the street happens at a faster pace and with a latin rhythm. When I left the hotel at 4:00 AM to catch my flight, the party was still going on.

At the end of the trip I wound down at the incredibly beautiful Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables, designed by New York architects Schultze and Weaver in 1925, the year after they completed Havana’s Hotel Seville (where we had dined in their rooftop restaurant).

At the Biltmore, New York sophistication and Spanish romanticism are still wed, still youthful, and still resplendent in their finery. Walking around the Biltmore, I could sense what Leonard Schultze and Fullerton Weaver had carried away from their time in Havana at the height of its Republicanera elegance. I felt like a special initiate, although the American conventioneers and local Chamber of Commerce types deaden the natural timbre of the place like a cloaked bell.

____________

Between these bookends of my trip lay Cuba – an encyclopedia of beauty and grace, even amid the wreckage of the Socialist experiment.

I always have thought of Socialism as more of a hypothesis than a political system – and in that regard it has served mankind well. I think history will be kind to the Socialists, once their story has been boiled down to their real-world role of counterbalancing the excesses of capitalism and refining worldwide structures of political economy. I think the mythology of the Marxist utopia – as well as our fear and loathing of that vision – will gradually subside as time goes on.

In this context, I walk away feeling that the Cubans have succeeded in their revolution. They really have achieved the things that they brag about in community health, broad-based educational opportunities, and a measure of justice for the average person after generations of exploitation. These are big achievements that are unmatched elsewhere in the Caribbean or Central America.

At the same time, they clearly have failed in the areas where Socialism can be expected to fail – in capital formation, entrepreneurship, personal freedom, and institutional accountability. These are big things to fail at, but nonetheless Cuba has shown that a third-world society can function – even in the jaws of a U.S. economic vice – without resorting to free trade zones, child labor, and the impoverishing strictures of the International Monetary Fund.

We all debated the merits of Cuban socialism, and in these debates I was among the defenders of their experiment. I remain a defender of the revolution, but Socialism can never be at the root of Cuban culture because it is incapable of placing special value on beauty.

Somehow, the world always seems to get uglier under Socialism, since all the mysteries and meaning in life have to be reduced down to common denominators of economic theory. Clearly this is unacceptable to the Cubans, who can never be the “new men” and “new women” of Socialism because they have no intention of being remade. They are much too interested in the timeless, the unquantifiable, the sensual. Their passions don’t encompass production quotas, and the things they do best are the things that involve the longest memories.

____________

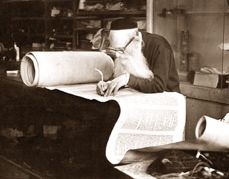

Nothing was more Cuban to me than the Partagas cigar factory. Some of use didn’t like the working conditions that we saw, and admittedly they were very rudimentary and old-fashioned. Having worked in an old-fashioned factory myself (so many years ago) that depended upon people more than technology, the place seemed strangely familiar and I found myself looking instead at the way people related to each other and to their jobs.

There was a tenderness to the place, as people literally spend years sitting next to each other delicately assembling these brown phallic objects whose only purpose is to give pleasure. The Spanish, the Americans, the Russians can come and go, but the Cubans hand this skill down from generation to generation like a secret handshake.

____________

But if any outsiders are to be loved it is the U.S.A. Americans. As many of us noted, the 30-year Russian presence blew out to sea leaving hardly a trace – except for some falling-apart concrete buildings and the Lada cars that are being gradually cannibalized to preserve the Cubans’ beloved Chevies and Buicks. I visited Meyer Lansky’s Riviera hotel, built in the 1950’s and seemingly preserved throughout the Russian era in meticulous detail – right down to the futuristic sculptures and the gangster photographs on the lobby wall. I couldn’t help wondering how the Cubans explained all of this to the Russians.

America long ago found its own affinity for Cuba, and like Robert Redford at the end of the movie Havana, looks out across the Florida Straight wondering if they will meet again. Generations of clunky, Calvinistic Americans found themselves embarrassed and titillated by the Cubans, and so they came for honeymoons and escapades. Others, who stayed longer, seem to have been those who had broken through to find an underlying state of grace that was hard to achieve in their own country. Hemingway was one of those – or was he? Who knows.

In short, the Cubans and the Americans are like old lovers. Neither of them likes what the other has been doing lately, but each will forgive all in hopes of finding that old groove.

____________

Cuba’s architecture is varied and eclectic, but the thing that comes through most strongly is the skill and sophistication that was applied to design. Whether dating all the way back to the Mudejar craftsmen of the sixteenth and seventeeth centuries, or from the neoclassical architects of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, there is a sense of proportion, and a love of beauty, that reveals itself in a powerful, palpable way. Cuba’s architects carried with them the gracefulness of their homeland, even when copying what they saw in Architectural Record or using the tools learned from their training in the United States or France.

A small but striking example of this is the University in Havana, which emulates the main plaza of the Columbia University campus. The seated Alma Mater statue, at the top of a long stair, directly recalls Daniel Chester French’s similar statue at Columbia. But where French’s Alma Mater is an austere and imposing lady, wearing multiple symbols of authority, the Cuban Alma Mater is an exquisitely soft and beautiful young woman.

Cuba’s monumental building tradition seems to have climaxed in its Capitol building. Again, the basic form of the building could be seen as derivative, and its heavy-handed purpose as the symbol of Cuba’s corrupt Republican governments comes through all too easily. But every element of the building is designed and put together with a graceful hand and an exquisite sense of proportion. Also, the design sensibility is carried down to the tiniest detail making the building a tour-de-force of architectural craft.

Older buildings, built before Cuba started sending people abroad to be trained as architects, express this love of beauty and this innate sense of grace and proportion even more strongly. I think of Spanish colonial architecture as being intensely masculine in character, with blunt forms and a strong sense of reserve. Cuba’s colonial buildings certainly are part of this tradition, but they permit another sensibility, more delicately and gently crafted, to overlay those strong and simple forms. The tradition of wall painting – both inside and outside – is something that we can only speculate about today, but I fantacize about how the streets and rooms of Havana or Trinidad might have looked with delicate overlays of painted decoration. Also, the ever-present arcaded loggias, recessed into the street walls of the buildings, blend the street and its buildings into a spatially complex and people-friendly environment.

____________

The decline of Cuba’s urban buildings during the revolutionary period is a terrible penance for Cuba’s colonial and neocolonial sins – and it is truly a form of penance, since the government in classic revolutionary fashion took resources away from the affluent cities to build up the quality of life in the countryside. The irony, of course, is that despite genuine improvements in rural life people continue to leave the countryside to take their chances in the cities.

This is not a problem unique to Cuba; throughout the third world the cities are overloaded with people and ramshackle, ad-hoc housing is the norm rather than the exception. In revolutionary Cuba, though, the ad-hoc housing is not in a pestilential ring around the city. Instead the palacios of the privileged and even the speculatively-built trophy houses of the affluent middle class were turned to the task of housing as many people as possible through informal ingenuity. This is a good thing if you want the working people of the city to “own” and occupy it, and to have access to the infrastructure of pipes and wires, streets, and services that the privileged previously had reserved for themselves. It makes for a sizable problem, though, if you want those buildings to last long enough to serve future generations, to let them reveal the beauty of their design, or to permit them to contribute to a long-term cultural or historical understanding.

It’s astounding what bad condition some of these buildings are in, and to see the crude concrete block partitions that have been used to make palacios into tenements. In some cases what had been elegant private patios have become dead-end alleys leading into the warren of makeshift apartments.

And yet the sense of grace that pervades this country extends even into those tenements. A truly memorable visit was to La Guarida (the “Strawberries and Chocolate” paladare), jammed into a corner of the ruined interior of a grandiose palacio. And although our opportunities to see beyond the street walls of peoples’ houses were limited, I saw enough to be impressed by how clean they were; how a sense of order was established amid the chaos of ad-hoc constructions.

Where the Cubans have started to restore their historic buildings, it seems to me that they are serious about balancing their social mission of having a living, working-class city and meeting the World Heritage standards of restoring and displaying their cultural history. I agree, though, with Rachel’s concern that newer city neighborhoods – especially in Havana – that do not meet the government’s test for historic preservation still need some kind of stabilization if they are not to literally fall down. And many of these areas contain late nineteenth and early twentieth century buildings of great quality, which in another society would be seen readily as having historic value.

____________

Finally, as a tourist I hope that Cuba will soon find other ways besides tourism to get money. It’s easy to see that the tourists and their dollars could overwhelm the fragile successes of the revolution, and leave only its failures as a legacy.

Whatever may come in the future, I have faith that the Cubans will not lose ownership of their special state of grace. It was never for sale during the Colonial and Republican periods (although the raunchy efflorescence of it certainly was), and I’m sure the Russians never even noticed that it was being withheld.

After all, a country that includes naked pagan dancing and 1950’s American cars as protected elements of its national patrimony, while empires enter and exit and everything else falls apart, is a place whose passions, at least, have not been misplaced. I wish them well, and I hope I get there again.